By Dominic Lapointe, Jacinthe Ouellet and Katia Nelson

Over two years have passed since the start of the pandemic, and many of our clients are suffering from mental exhaustion, also referred to by experts as pandemic fatigue.

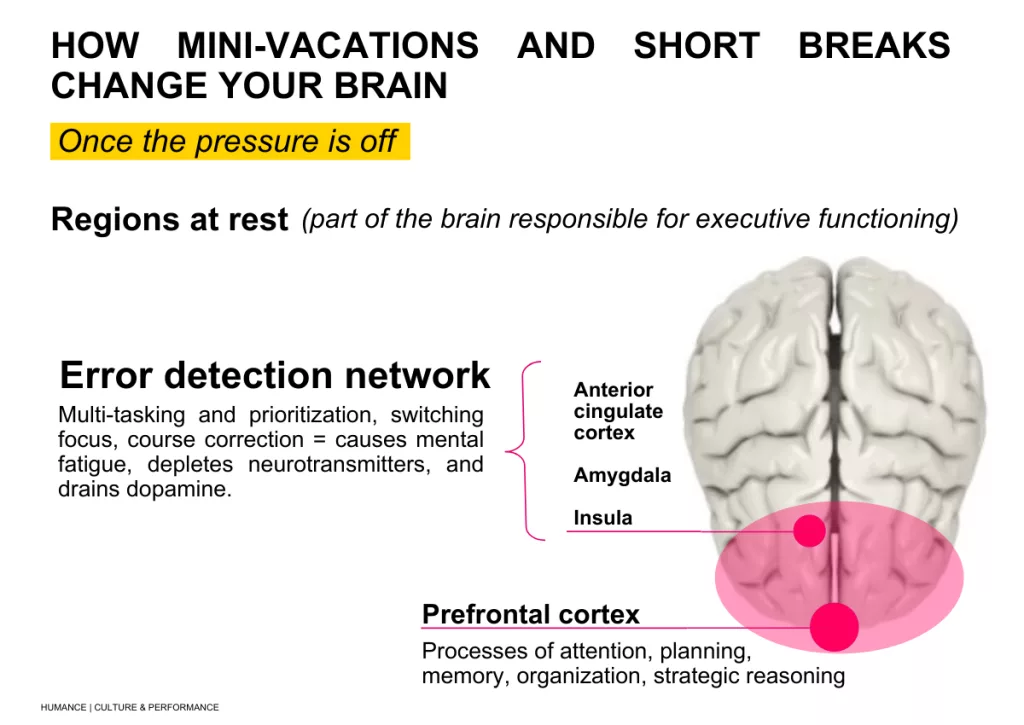

In these uncertain times—even for those of us who are naturally agile and thrive on change—this never-ending emotional roller coaster we seem to be on is exhausting. Adapting to health measures, social distancing, adjusting to the needs of our loved ones and conflicts raised by the situation, not to mention the new reality of work (from an operational standpoint) and remote work have come together and created a perfect storm for mental exhaustion. Work and school have permeated our personal lives, creating issues in terms of our boundaries. While some of us may have adjusted well to this new work reality, many still struggle to strike the right balance to recover or even to simply confront it. Most of our clients have adopted a breakneck pace, which has given them a sense of hyper-productivity. However, they no longer give themselves breaks the way they once did—by physically moving from one geographic location to another or having impromptu chats with colleagues around the water cooler. As a result, they never quite relax, and their frontal lobes remain on high alert 24/7. Clients report feeling guilty and don’t give themselves permission to unplug.

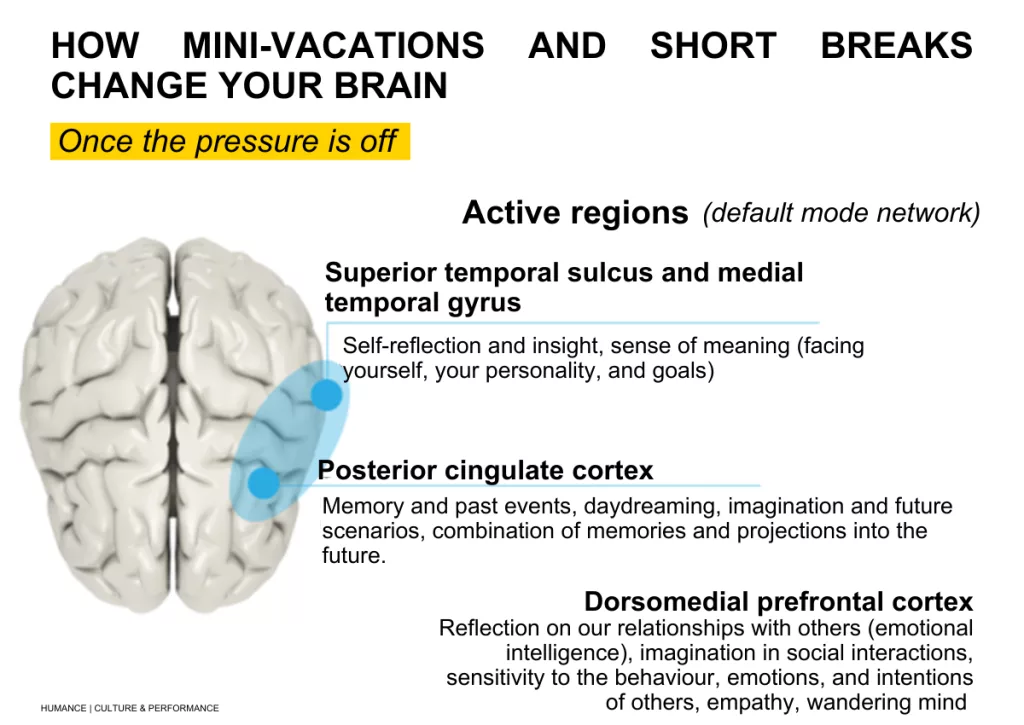

Although humans have evolved over time and developed tools to handle major stressors, resting between sprints is essential to recover and maintain vitality over time. These days, however, it’s easy to forgo downtime and let yourself get lost in the shuffle. Studies in neuroscience show that taking short breaks every 90 minutes and 30-minute solo mini-vacations dedicated to energizing activities (e.g., singing, taking in the arts, listening to music, laughing, doing a jigsaw puzzle, playing, cooking for fun, knitting, crafting, drawing, gardening, celebrating, dancing, etc.) gives our frontal lobes some much-needed rest, stimulates the lateral regions of the brain responsible for daydreaming, development of insights, and emotional intelligence, and promotes neurogenesis.

The science offers strategies to refocus and recover from stressors while boosting resilience. Here are a few proven tips to return to basics: spend time in nature, improve sleep quality and duration, and exercise regularly.

Spend time in nature

Because their very survival depended on it, our ancestors evolved to have a deep knowledge of and connection with nature. Studies on the subject show that being close to nature increases our sense of well-being, happiness, positivity, and meaning in our lives while decreasing psychological distress (1). It also produces a calming effect and helps us carry out cognitive tasks more efficiently (2).

Getting the most out of nature

While there are no hard-and-fast rules, research shows that spending 120 minutes in nature on a weekly basis produces optimal benefits to health and well-being (3). However, if that’s not possible, less is still better than none. One study showed that the most effective way to reduce your cortisol (the body’s main stress hormone) levels is to spend 20 to 30 minutes walking or sitting in nature (4). Alternatively, you can garden, stroll through a park, or enjoy the local flora in your neighbourhood. You can also boost the benefits by being fully present—in the here and now—and in tune with all five of your senses.

Improve the quality and duration of sleep

In the hustle and bustle of everyday life, sleep can often fall by the wayside. However, this key element of our well-being and performance recharges the brain, improves our ability to learn, and helps us retain information and memories (5). Reduced cognitive performance and increased interpersonal, mental, and physical health problems are often attributed to lack of sleep as well.

Getting the most out of sleep

Duration: 7–9 hours of sleep are recommended per night (6). While this amount of sleep has been found to improve longevity, sleeping more than 9 hours tends to have the opposite effect.

Quality: to enhance deep sleep (a typical night’s sleep consists of three to six sleep cycles of 90 to 120 minutes, alternating between light and deep stages) and promote recovery, experts recommend implementing sleep hygiene strategies.

- Wake up at roughly the same time every day and go to sleep as soon as you begin to feel tired. Establish a bedtime routine to promote sleep.

- Practise diaphragmatic breathing (taking air into your belly rather than your chest) to reduce your heart rate.

- Avoid caffeine 8–10 hours before bedtime.

- Avoid hectic environments 1 hour before bedtime.

- Avoid bright light sources (particularly from screens) between 10 p.m. and 4 a.m.

- Give yourself permission to digitally disconnect for prolonged periods of time. Avoid information and communication technology overload during the day.

- Take short naps or limit them to under an hour.

- Keep your bedroom temperature cool. Our body temperature goes down between 1 and 3 degrees during sleep and a warm room is a common cause of night waking.

- Avoid alcohol, sleeping pills, and THC, all of which can hinder deep sleep. Drink plenty of water during the day.

- Write down any recurring or intrusive thoughts you may have before bed to keep them at bay while you sleep. You can focus on them when you wake up. Be sure to also write down any good ideas that come to mind to remember them.

- If you experience insomnia, consult a health care professional.

Exercise regularly

While too often overlooked, physical exercise is another excellent way to promote well-being (both short and long term) and reduce depression and anxiety (8). From a biological perspective, physical activity protects the brain and improves mental health by increasing serotonin and endorphins (neurotransmitters also referred to as happy hormones), promoting the growth of new neurons, and improving the quality of sleep. From a psychological perspective, regular physical exercise also tends to enhance our sense of accomplishment and resistance to potential stressors. In addition to promoting well-being, exercise is also known for increasing cognitive ability by reducing inflammation and promoting blood flow to the brain (9).

Getting the most out of exercise

Be realistic: choose activities that suit your fitness level and schedule. As Jean de la Fontaine wrote in his fable The Tortoise and the Hare: “There is no use running; you have to leave on time.” In other words, start with a simple and achievable goal. If your goal is too ambitious, you will need to make adjustments. The risk of injury is another consideration, so remember that consistency is more important than performance. For someone with a sedentary lifestyle, walking regularly for 30 minutes at a moderate pace is a good place to start. Stretching is another activity that’s easy to do at home. For those who work from home, taking breaks from cognitive tasks every 90 minutes and doing a dynamic activity such as going to the post office, walking around the house, or doing a load of laundry is recommended.

Overall, Health Canada and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US recommend incorporating 150 minutes of medium-intensity activity into your weekly routine. Exercise is considered medium intensity when your heart rate increases and you sweat, but can still carry on a conversation (10).

What are your strategies for recovering from mental exhaustion?

Take a few minutes to look inward and write down the emotions you’re feeling in this moment. Also, write down your answers to the following questions:

- On a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being very low and 10 very high), how would you rate your level of mental exhaustion?

- How does this score reflect your current state of mind?

- What are your energizing strategies to take care of your physical and psychological health?

- What would you like to start doing?

- What do you already do well and what do you want to continue doing?

- What should you stop doing to take care of your physical and psychological health?

Interested in taking things a step further with the guidance of a professional?

Humance, with its team of professionals, organizational psychologists, and coaches, can help you implement motivating and meaningful strategies to overcome mental exhaustion and improve physical and psychological health.

Reach out to our experts:

- BRATMAN, G. N. et collab. (2019). « Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective », [En ligne], Science Advances, 5 (7). [https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aax0903].

- WEIR, K. (2020). « Nurtured by nature », [En ligne], American Psychological Association, 51 (3), 50. [https://www.apa.org/monitor/2020/04/nurtured-nature].

- WHITE, M. P. et collab. (2019). « Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing », [En ligne], Scientific Reports, 9, 1. [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-44097-3].

- HUNTER, M. R., GILLESPIE, B. W., YU-PU CHEN, S. (2019). « Urban Nature Experiences Reduce Stress in the Context of Daily Life Based on Salivary Biomarkers », [En ligne], Frontiers in Psychology, April 4. [https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00722].

- AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION (2014). « Getting a good night’s sleep: How psychologists help with insomnia », [En ligne]. [https://www.apa.org/topics/sleep/disorders#:~:text=Sleep%20is%20vital%20to%20our,problems%20with%20mood%20and%20relationships].

- HUBERMAN, A. et WALKER, M. (2021). « The science & practice of perfecting your sleep », [En ligne], Huberman Lab, August 2. [https://hubermanlab.com/dr-matthew-walker-the-science-and-practice-of-perfecting-your-sleep/]

- HUBERMAN, A. (2021). « Toolkit for Sleep », [En ligne], Huberman Lab Podcast Neural Network, September. [https://hubermanlab.com/toolkit-for-sleep/].

- WEIR, K. (2011). « The exercise effect », [En ligne], American Psychological Association, 42 (11), 48. [https://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/12/exercise].

- HARVARD HEALTH PUBLISHING (2021). « Exercise can boost your memory and thinking skills », [En ligne], February 15. [https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/exercise-can-boost-your-memory-and-thinking-skills].

- HUBERMAN, A. (2022). « The science of making and breaking habits », [En ligne], Huberman Lab Podcast, January 3. [https://hubermanlab.com/the-science-of-making-and-breaking-habits/]

- LACHAUX, J.-P. (2015). « Le cerveau en vacances : comment régénérer ses neurones en été », Cerveau & Psycho, Juillet, no 70.